By Jason

Togyer

Copyright © 2006, all rights reserved.

It was

3:43 p.m. when Fire Chief David Fowler, sitting in his office in

the

McKeesport Municipal Building, spotted the smoke.

"Oh my God, the Famous is on fire," he said, getting to his feet.

The old department store building was only a block from the fire

station. Fowler's crews were on the scene within minutes, pouring water

onto the building, and reinforcements were soon roaring into the city

from throughout the Mon Valley.

But all of their efforts seemed to be for nothing.

Fueled by high winds, the flames leapt from The Famous to the Elks

Temple next door on Market Street. Debris and flames rained down on

Kadar's Men's Store across Market, setting it ablaze. Then the fire

jumped to the old Riggs Drug Store.

Within an hour, McKeesport's entire main street, from the Penn-McKee

Hotel to the old Memorial Theater, was ablaze. The winds carried

burning embers throughout the city and suburbs.

Soon, fires were breaking out on rooftops as far away as White Oak and

North Huntingdon Township. Residents manned garden hoses and bucket

brigades to douse them before they could do more damage.

When

the smoke cleared on the night of May 21, 1976, two blocks of

Downtown McKeesport were all but gone. Seven buildings were declared

total losses and at least two dozen others sustained damage. Estimates

of the total losses topped $5 million. While some of the damaged

businesses would eventually relocate and reopen, a few—including

the theater—would not.

When

the smoke cleared on the night of May 21, 1976, two blocks of

Downtown McKeesport were all but gone. Seven buildings were declared

total losses and at least two dozen others sustained damage. Estimates

of the total losses topped $5 million. While some of the damaged

businesses would eventually relocate and reopen, a few—including

the theater—would not.

And only one of the fire-damaged structures would be rebuilt. For the

first time that anyone could remember, large empty lots in Downtown

McKeesport—in prime locations—remained vacant.

The massive fire that damaged Downtown McKeesport that May wasn't a

mortal blow to the city's business district. But it was arguably the

first major setback in a long series of events that eventually gut the

once-bustling commercial center of the Mon Valley.

A Downtown In Decline

Indeed, Downtown had been in a slow decline for at least a decade,

as shoppers drifted off to suburban shopping centers like Monroeville

Mall and Eastland in North

Versailles. The city fathers had fought back

with a number of projects designed to attract people back Downtown.

Since parking in the congested area around

Fifth Avenue had

always been a problem, a new garage was opened on Sixth Avenue to

supplement the one on Lysle Boulevard. Stores stayed open late on

Thursday nights to attract people after work.

When the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad rerouted its tracks around the

area, eliminating the frequent grade crossing tie-ups Downtown, the

city's Redevelopment Authority swung into action, condemning a slew of

old brick and wood stores and warehouses between

Sinclair Street and Tube Works Alley, and tearing them down. In their

place rose the Midtown

Plaza Mall—a $6 million enclosed shopping center and apartment

building with its own parking garage—and the Executive Building, an

office and retail complex with a built-in mini-plex movie theater.

But they were competing under several handicaps. For one thing, the

parking garages came with bonds that had to be paid off. The city,

suffering a financial crisis that forced it to lay off 12 police

officers and dozens of other employees late in 1975, could hardly

afford to pay the debts itself. So, the garages had to be financed

through user fees. Parking at the malls, naturally, was free.

Then, too, there was a lingering perception that Downtown was "unsafe."

McKeesport officials pointed out that there were thefts and muggings at

the shopping centers, too—they just didn't make the newspapers.

And no matter what McKeesport tried, there would still be one thing

that malls had that the city just couldn't offer: The malls were shiny

and new.

Parts of McKeesport's Downtown still looked much the same as they did

in the late 19th century. A nationwide craze for "gentrification" and

preservation of old buildings was still several years away. For now,

Downtown McKeesport's main streets, the pride of the entire valley

after World War II, just looked tired and old.

Bright Spots Amid The Darkness

McKeesport was hardly alone, of

course. Cities across the Northeast

of nearly every size were fighting the same trends toward suburban

malls, with varying degrees of success.

And there

were bright spots, to be sure. Robert M. Cox, president of Cox's

Department Stores (itself opening branches in suburban malls by

that

point) completed a multi-million dollar expansion of his flagship store

in 1972. Wander Sales, a local chain of television and

appliance stores, erected a nice new building on Fifth Avenue across

the street from the Executive Building. A new Sheraton Hotel opened on

Lysle Boulevard, featuring one of several "Red Bull Inn" restaurants in

the Pittsburgh area. And the Midtown Plaza Mall, though it lacked a

large "anchor" tenant, was full of life.

Plus, even if Downtown McKeesport no longer drew many shoppers from the

suburbs, it still had a large captive population of office workers and

professionals every day. The old People's Union Bank Building—by

then owned

by Pittsburgh's Union National Bank—was full of doctors and

lawyers. So was the smaller McKeesport National Bank Building a few

blocks away. G.C. Murphy Company, a chain of more than 500 variety and

discount stores located up and down the Eastern Seaboard, employed

1,000 people at its headquarters.

Each morning, thousands of people arrived Downtown to go to work; many

stopped for breakfast on the way. At lunchtime, they poured onto the

streets, many to go shopping. And many others stopped off for a drink

or dinner on the way home.

And three times a day, shift change at U.S. Steel National Plant sent

thousands of people out into the streets of Downtown McKeesport. While

most of the 7,000 mill employees were no longer walking or taking

buses home—they were living out in North Huntingdon Township, and

driving to and from the

mill—a considerable percentage still spent

some time Downtown.

Indeed, the situation seemed hopeful enough for several private

developers to take a chance on the city's future. One was former city

councilman Michael Newman, owner of the Penn-McKee. Newman's political

career had been torpedoed by his conviction a few years earlier for

allegedly tapping the phones of one of his political enemies. But he

was far from finished, and he had big plans for the corner of Fifth and

Market—and the old Famous.

The Famous: McKeesport's 'Big

Store'

The Famous—"McKeesport's Big Store," as it billed itself—was

the descendant of a dry goods store called Skelly's, which opened in

1897 inside the Oppenheimer Building, completed a few years earlier. In

1915, Skelly's was purchased by the Katz and Goldsmith families, who

owned The Famous Department Store in nearby Braddock. The McKeesport

store took the parent company’s name.

A few years later, as the Katzes and Goldsmiths got ready to expand The

Famous, tragedy

struck.

Early on the morning of Sunday, Feb. 8,

1920, a fire began

at the People's Ice Company on Fifth Avenue, then spread to the

neighboring Crown Chocolate Co. factory at the corner of Fifth and

Strawberry. From there, the flames leapt to the adjacent Famous. The

blaze, which did $1 million damage, was, ironically, the largest fire

in McKeesport history—until 1976.

The 1920 fire didn’t keep The Famous closed for long. The renovated

store opened to customers by Aug. 26. The Katzes and Goldsmiths then

purchased a neighboring lot on Market Street, along with the adjacent

Edmundson Building, and constructed a five-story addition to The

Famous.

This new, larger store opened for business Oct. 25, 1926, and

McKeesporters were

bursting their buttons at the sight of it. The addition "makes The

Famous the largest store in Western Pennsylvania between Philadelphia

and Pittsburgh," reported The Daily

News in an article that, perhaps,

was a little too

enthusiastic. "It is truly a metropolitan store and

offers to the people of this community the most desirable, quality

merchandise at prices that are always lower than the average."

Still, what was high-cotton in 1926—wooden floors, brass railings,

tin ceilings—was old hat and corny in the 1950s. In April 1955, The

Famous was sold to the Pittsburgh

Mercantile Company, the former "company

store" at the Jones & Laughlin Company’s steel mill on the South

Side of Pittsburgh, and The Famous was modernized—externally, at least.

New blue tiles were attached to the facade,

in imitation of Cox's.

But Cox's, and other stores Downtown, clearly outclassed The Famous,

which was no longer competitive. It was sold again in 1962 to a company

called Mutual Industrial Sales Co., or "MISCO," a membership-only

discount store. MISCO failed in 1965. Another

discounter, Gold Coast

Stores, moved into the building in September 1968, only to close a

short

time later.

Hope—Then Tragedy

Then came Newman. He announced plans in

1973 for a $400,000 building

project that would rehabilitate both the Penn-McKee and the old Famous.

Most of the Famous was to be torn down, with only the newer parts of

the building left standing. Those would be turned into a shopping plaza

and parking lot, which would be integrated with the hotel.

|

|

|

|

|

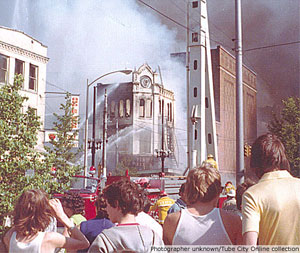

Firefighters struggle in vain to control the wind-whipped blaze at The Famous. |

In January 1976, Newman

purchased the building that had housed The Famous from the Oppenheimer

family for $97,000. When

spring came, crews from Potterfield & Ritenour Co. of Connellsville

moved in, and began demolishing the structure.

On the afternoon of May 21, they were on the roof of The Famous, using

cutting torches and saws to take apart a 2,000-gallon water tank. It

was a nice day for the work—sunny and mild, if a little bit breezy.

Officials later speculated that pieces of hot metal from the water tank

fell onto the roofing tar and smoldered for some time.

Suddenly, those pleasant breezes whipped

the smoldering tar into flames.

Across the street at the state liquor

store, clerk

John Hvoszik saw smoke on the roof of The Famous. "Then in a couple

of seconds, it started to smoke like hell, and in another minute, it

was really flaming," Hvoszik said.

The demolition crew escaped down the steps

and to the street as Chief Fowler spotted the fire and

sounded the alarm.

But fighting the blaze at The Famous

wouldn’t be easy. To aid the demolition, the wrecking crews had cut

holes down through the roof

and the floors of the building, so that equipment and debris could be

passed up and down. Now, those passageways acted like chimneys,

feeding air to the flames.

And though the building had a steel

skeleton and

a brick and terra cotta facade, everything else inside was inflammable.

Over many years and several owners, layers of new plaster, wood and

lath had been hung over top of the old walls and ceilings of the

old Oppenheimer Building. Now, the dry building materials burned quick

and

hot.

The flames leapt the alley to the Elks

Temple next door. The old Market Street School,

recently used by Community College of Allegheny County as a satellite

campus, caught fire next. The Penn-McKee Hotel was evacuated.

Flames Whipped By Wind

More fire companies were called for assistance, but the wind blew

harder. Across Market Street, to the east of The Famous, was Kadar's

Men's Store. Though the business was fairly young by McKeesport

standards—about 35 years old—the building wasn't. Built in the

mid-19th century, it was a city landmark, thanks to the big "silver

dollar" that decorated its cornice.

A salesman at the Clairton branch of Kadar's, hearing of the fire in

McKeesport, called the store anxiously. "It's fine," he was told.

He called back a few minutes later. We're still OK, they said. He

called back a few minutes later. A recorded message told him the number

was out of service.

The front windows of Kadar's had blown out, and the store was ablaze,

too.

"It was the most terrifying scene I ever witnessed," Al Kadar said the

next day. "Every window of the store was framed with fire. It was

unbelievable."

|

|

|

|

|

Spectators watch as Kadar’s is engulfed by flames. |

From Kadar's, the flames moved to the

Farmer's Pride poultry market

next door, and then to Coney Grill. Soon, all were burning furiously.

Although the flames scorched the sides of the former Memorial

Theater—recently gutted and turned into a "twin theater" called the

McKee

Cinemas—the heavy brick walls of the fireproof auditorium prevented

the fire from moving further east on Fifth Avenue.

There was no such barrier to keep the fire from reaching The Apple

Shop Too, located in the old Riggs' Drug Store, catty-corner to The

Famous. Next went Oddo's Hobby Shop, Book Sale, Feig's Bakery, Natale's

Sporting Goods, and the Music Box, a record store less than a year old.

Owner Wayne Simco only had time to grab the cash drawer and his

electric guitar before the store burst into flames.

'This Was a Firestorm'

And still the winds kept shifting. Police cordoned off streets, only to

have the winds change direction, carrying the flames behind the safety

lines. One police officer responding to the disaster parked his

personal car on Sixth Avenue, sure it would be safe; he returned a few

hours later to find the vinyl top melted. At the corner of

Sixth and Market, the heat blistered the white paint from the front of

the century-old Hunter-Edmundson-Striffler Funeral Home.

"This was a firestorm," Chief Fowler said later. "It went from The

Famous across Market Street like a tornado. The Famous was down within

a half-hour, and Kadar's went right away. ... I've been a fireman 29

years, and I never saw anything like this."

The demand for water was sucking hydrants dry. Hoses were snaked down

Fifth Avenue to the riverfront at Water Street, where a pumper engine

drew water from the Youghiogheny.

At Mon-Yough Fire Defense Council, orders went out for an

"all-call"—every single fire department in a 15-mile radius was to

respond. For more than an hour, the air was split by the sound of civil

defense sirens, wailing across the valley to alert volunteer

firefighters and rescue personnel.

Relations between the city and the surrounding boroughs and townships

hadn't always been pleasant, but no one refused this plea for help.

"There was no

'we' and 'they,'" one exhausted volunteer told The Daily News. "It was

more like man against the elements."

More than 40 companies answered the call; in all, 1,000 members of the

fire service from

across the Mon Valley were involved in the effort.

"Maybe some of the people in City Hall will learn to quit insulting the

surrounding communities," City Councilman Thomas O'Neil said.

And not all of the rescuers were fighting the fire at the corner of

Fifth and Market.

The winds spreading the flames were carrying large chunks of burning

wood and roofing tar across the city, and now, new fires were reported

all over McKeesport. An old warehouse in the Third Ward burst into

flames. Two houses on Jenny Lind Street were burning as well, as were

several homes on Ninth Avenue.

Four blocks south on Walnut Street, the Salvation Army mobilized to

provide aid to the firefighters—only to have its

building catch fire, too. Volunteer firefighters from Coulter poured

water onto the roof, and onto the post office across the street.

National Guard Mobilized

With Downtown becoming chaotic, police threw up

roadblocks on Walnut Street at the 15th Avenue Bridge, West Fifth

Avenue at Rebecca Street, and Lysle Boulevard at Coursin Street. The

Pennsylvania Army National Guard rolled into town to help keep the

peace, along with county sheriff's deputies and state troopers.

|

|

|

|

|

Onlookers and gawkers sought vantage points across the Mon Valley. |

Except for fire trucks and police cars

screaming through intersections,

responding to calls, traffic in Downtown McKeesport ground to a halt;

Port Authority buses trying to leave the city were trapped for up to

four hours, while those trying to enter the city were turned back. A

reporter for The

Pittsburgh Press spotted a long line of

men in business suits, queued up at a Fifth Avenue phone booth, calling

home to report they'd be late.

Yet despite the police presence, the fire drew hundreds of spectators

who might otherwise have been shopping or seeing a movie Downtown on a

Friday night. Bystanders clogged the approaches to the Jerome Avenue

Bridge.

Indeed, since the smoke and flame could be seen for miles, viewers

crowded onto any high point that offered a view—Romine Avenue in

Port Vue, Skyline Drive in West Mifflin, the parking lot at Eastland

Mall. From the Boston Bridge, four

miles away in Versailles, onlookers stared transfixed at the column of

black smoke rising from the northwest. Some people reported that the

mood of the bystanders was festive.

The mood was not as jovial Downtown, where businessmen and residents

alike were breaking down into sobs while watching the calamity.

Some just stared, open-mouthed, at what

they said looked like the

aftermath of the incendiary bombing raids on Europe during World War II.

"Everything I have" went up in smoke, said Larry Ruttenberg, owner of

Book Sale. Ruttenberg had been planning to move to a new building, so

was carrying only $10,000 in insurance; his inventory alone was worth

10 times that. "I'd need $50,000 to

start again," he said. "Where am I going to get that? What am I going

to do? This

was my whole life."

Extent of Damage Becomes Clear

By midnight, calm was starting to return as firefighters brought the

last of the fires under control. And a few hours later, as city council

met in emergency session, the morning sun revealed the true

extent of the damage.

Only the twisted steel skeleton of The Famous was still standing.

Kadar's was a pile of debris. A few walls remained of the other

buildings. The heavy masonry shell of the Elks Temple, built in 1904,

was intact, though the interior had collapsed.

On the outside, the McKee Cinemas seemed to have withstood the flames

in good shape,

but inside, water and smoke had taken their toll. A beautiful showplace

when it opened in 1927, the theater had already been relegated to

showing

soft-core porn and foreign films. Its owners decided it wasn't worth

repairing the damage.

The names of the features were removed from the marquee, and letters

reading "Closed

Till Further Notice" went up in their place. Those same letters

remained

on the sign until the theater's demolition in 1985, waiting for a

further notice that never came.

Other buildings, though damaged by smoke and water, were more

fortunate. Immanuel Presbyterian Church, built in 1902, had water

damage to its basement and smoke throughout, but it would be cleaned

and repaired. The Penn-McKee—years past its prime, now a residence

for transients and businessmen—would reopen as well.

By mid-morning of the day after the fire, bulldozers were chewing

through the piles of debris. Within a few weeks, the demolition was

complete.

State, Feds Rebuff City’s

Pleas

And then, as if the fire hadn't been bad enough, McKeesport discovered that a nasty coda was attached—the city was going to receive almost no help from the county, state or federal governments.

Gov. Milton Shapp had toured the fire

scene only five days later. “It looks like a disaster area,” he told

Mayor Thomas Fullard, assuring him, “We'll get some help here.”

Shapp's word was good for less than a week.

On June 1, his administration sent a letter to Fullard.

Shapp’s Deputy Secretary for Community Affairs told the city that the $5

million loss was not of “such severity and magnitude” that McKeesport

couldn't handle the cleanup itself, at least in the state’s opinion.

The impact of the fire that had gutted two

blocks of Downtown McKeesport was not of “such magnitude to

warrant” a declaration of disaster, the Shapp administration concluded.

The state even turned down an emergency request for $10,000 to

cover police overtime.

"I've never seen such bureaucracy in my life," Mayor Fullard told a

reporter. "I feel they're totally full of ... whatever."

Worse yet, the state's refusal to act was cited by the federal

government as the reason that it

couldn't (or wouldn’t) help either. In the days following the blaze,

U.S. Rep. Joseph Gaydos and others had promised that a million

dollars in emergency federal aid would soon be on the way.

But because of the state’s rejection of

McKeesport’s requests, only $100,000 came—a grant from the Department

of Housing

and Urban Development to reimburse the city for cleaning up areas that

were already targeted for urban renewal

before the fire.

To add insult to injury, one HUD official said that McKeesporters

should be happy about

the disaster. It had created “some prime real estate in the Downtown

area,”

he said. “Let’s work on the idea of turning adversity into advantage

for McKeesport.”

Another federal agency, the Small Business Administration, offered

loans to business owners—but on the same terms they would have provided

before the fires

destroyed the incomes the businesses produced.

Under those conditions, the loans

were worse than useless. The merchants had no ability to pay them back.

"They didn't need help before the fire," Fullard fumed. "They were in

business then."

McKeesporters Press On

Nevertheless, those McKeesporters that could, persevered. Kadar’s and

Natale’s

relocated. “I can’t leave,” said Al Kadar. “This is a good city. I know

and like the people.”

On the site of The Famous, Elks Lodge No.

136 built a modern

new hall with a banquet facility and an attractive dance floor.

Declining membership eventually forced the lodge to sell the building,

and then

disband.

Some of the displaced stores, like Oddo's and Farmer's Pride, relocated

to the Midtown Plaza, but the sheen was starting to come off of the

massive mall, even though it was only a few years old. The lack of a

big anchor tenant left it without

a major draw, and soon the smaller stores were closing, one by one.

Derelicts started hanging out in the corridors until mall management

began locking the outside doors.

In 1979, Century III Mall opened in West Mifflin. With four major

anchors and more

than 100 other shops, the new facility sent Midtown Plaza and the rest

of Downtown into

an accelerated decline.

Then came U.S. Steel’s decision to close many of its Pittsburgh-area

facilities. The Duquesne Works closed in 1984, and its sister plant,

National Works soon followed, leaving 10,000 steelworkers unemployed.

Many moved away; those who stayed behind had little money to spend on

new clothes or jewelry in Downtown stores like David Israel or

Goodman’s. Meanwhile, stock speculators on Wall Street

fueled a bidding war for the G.C. Murphy Company, which found itself

the unexpected target of a hostile takeover

by Ames Department Stores. The Murphy offices soon closed, eliminating

another 1,000 good-paying jobs.

These were substantial blows that few

business districts the size of

McKeesport's could withstand.

In a Downtown area that had transacted $77 million in retail sales in

1948,

only a handful of businesses remained by the mid-1980s. Many of the

storefronts were empty. The doctors and lawyers who once packed

the office buildings joined the retail stores in the suburbs; the

offices they left behind either stayed vacant, or were rented to

agencies that served the poor

and elderly.

The Final Curtain

|

|

|

|

|

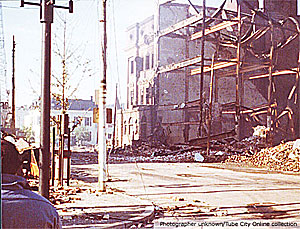

The aftermath: Seven buildings destroyed or heavily damaged, with more than two dozen others impacted. The final damage was estimated at $5 million. |

And the Memorial Theater, once a showplace

in the style of the major

urban movie palaces of the 1920s, had become an albatross instead of an

asset. The gloomy, boarded-up hulk loomed over pedestrians going to and

from the Sixth Avenue parking garage.

Except for some emergency repairs, the soot-blackened walls of its

massive auditorium looked much the same as they had the morning after

the fire—except that they were deteriorating with each

passing year.

Yet when the Memorial Theater was finally demolished, nine years after

the fire, a few people stood on Fifth Avenue and wept again—just as

they

had on the night of May 21, 1976.

They cried because the cranes ripping down

the

Memorial's walls had revealed a surprising, somewhat distressing secret.

It seemed that the remodeling effort to create the two "McKee Cinemas"

inside the Memorial's auditorium had left its ornate 1920s details

largely

intact.

False walls and ceilings had been erected

inside the originals. But above the cheap wallboard and fiber ceiling

tiles, gilded grape vines

still climbed Moorish columns. The mighty proscenium arch, though

injured in a few places, was otherwise as strong and graceful as ever.

And if you squinted through the swirling clouds of dust and debris, you

could make out the pale blue ceiling, once decorated with hundreds of

twinkling light bulbs to simulate stars.

It was as if the past glories of McKeesport—wiped away first by a

massive fire, then by a decade of corporate indifference—had come back

to taunt the city's people, one last time.

Sources:

Author's notes and interviews

Vertical file, ”The Famous," McKeesport Heritage Center, McKeesport, Pa.

Mike Anderson, ”'Everything I Have' Went Up In Smoke," The Pittsburgh

Press, May 23, 1976.

Robert S. Austin, ”Devastation Reported to Businesses," The Daily News,

McKeesport, May 22, 1976.

Stuart Brown, ”No Pa., U.S. Aid for McKeesport in Aftermath of Downtown

Blaze," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette,

Aug. 19, 1976.

James B. Johnson, ”'The Famous' Fire Compared to Previous Ice House

Blaze," The Daily News,

McKeesport, May 22, 1976.

Nicholas Knezovich, ”McKeesport Fire Rips Two Blocks," The Pittsburgh

Press, May 22, 1976.

Tim Martin, ”City Heads Meet, Plan Cleanup Action," The Daily News,

McKeesport, May 22, 1976.

Paul Maryniak, ”Fire-Blitzed McKeesport Grateful But Banking on U.S.," The Pittsburgh Press,

May 26, 1976.

Robert McHugh, ”McKeesport Begins Long Journey Back," The Pittsburgh

Press, May 23, 1976.

Regis M. Stefanik, ”McKeesport Fire Razes Seven Buildings," Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette, May 22, 1976.

Ray Steffens, ”Fire Turns Remodeling McKeesport Into Disaster Area,” The Pittsburgh Press,

May 23, 1976.

A McKeesport Commemorative.

McKeesport, Pa: McKeesport Bicentennial

Committee, 1976.

"Old Famous Store Facing Demolition in

McKeesport," The Pittsburgh Press,

Feb. 15, 1976.