By Jason Togyer

McKeesport Union Station? Elevated railroad tracks through Downtown? A mile-long tunnel? Those ideas were seriously considered during World War II, when the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad's 70 daily trains between Pittsburgh and Connellsville choked the city's business district.

It may be hard for younger readers to appreciate the disruption that McKeesporters endured on a daily basis, but the B&O's busy main line between Chicago and Washington, D.C., passed right through the middle of Downtown from the 1850s until May 6, 1970.

The railroad line was laid when McKeesport was a borough of only a few hundred residents, but the city grew up and over the tracks. It came up the Youghiogheny River through Versailles and Christy Park, entering Downtown McKeesport under the old 15th Avenue Bridge and traveling through the Third Ward between Market and Walnut streets. The smoke and noise were a constant annoyance for residents of that neighborhood, who were predominantly Italian and Slavic immigrants and African-Americans.

|

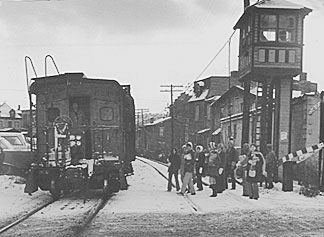

| This photograph from the 1950s shows a typical workday in McKeesport, with trains, passing in opposite directions, blocking both Lysle Boulevard and Fifth Avenue. (Photographer unknown; reproduced from photo in 1963 McKeesport redevelopment plan.) |

But when northbound trains reached the Ninth Avenue crossing, the problem became one shared by McKeesporters and non-McKeesporters alike who came to the city to work, shop, or visit one of the movie theaters, restaurants or taverns. The B&O's two-track main line cut diagonally across Downtown to the intersection of Sinclair Street and Lysle Boulevard. There, it joined the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad's lines along Fourth Avenue, which separated the National Tube Works from the rest of Downtown. (Beginning in the 1930s, the B&O had an agreement to use P&LE's tracks between McKeesport and New Castle to avoid its own hilly, curvy line through Pittsburgh. The P&LE's line followed the rivers and was mostly level.)

According to a 1945 engineering study, from Christy Park traveling north there were 28 grade crossings in McKeesport. On average, 70 trains per day passed through town. That didn't account for switching moves as the B&O picked up and dropped off train cars at various businesses, including Balsamo's Market, Crown Chocolate, Cudahy Packing Co., Ruben's Furniture, Peters Packing Co., Tube City Brewing Co., and the railroad's own freight house on Lysle Boulevard.

|

|

| Pedestrians wait for a train to pass before crossing at what looks like Tube Works Alley in this late '60s photo. (Photographer unknown, author’s collection) | |

Among the most aggravating and dangerous crossings in town were at Walnut Street near Sixth Avenue, and on Fifth Avenue near the B&O depot between Locust and Sinclair. Walnut Street was blocked, on average, for a total of three hours per day, while Fifth Avenue was blocked for four hours daily. At the time, McKeesport was home to an estimated 55,000 people, plus countless temporary war workers who weren't counted in the 1940 census. Another 100,000 people worked or shopped Downtown every week. At Fifth Avenue alone, 70,000 people and 2,800 automobiles crossed the railroad tracks every day.

Only the crossings at Locust Street, Lysle Boulevard (nee Jerome Street) crossing and Cliff Street (the entrance to Firth-Sterling Steel Co.) were protected by flashing lights and warning signals. At the other intersections, "crossing towers" were manned by watchmen, who stayed in their tiny booths and watched for the smoke of approaching trains. (In later years, electric buzzer and light arrangements alerted them.) Then, they climbed down the stairs or ladders and manually cranked the crossing gates to close the streets. Often times, jobs in the "crossing shanties" were given to old-time railroad employees who had been injured on the job and lost a limb, and thus could no longer hold down jobs as engineers or brakemen.

(One of the crossing towers can still be seen in a city park at Walnut Street near Sixth Avenue. Unfortunately, as of this writing, it's been painted into an incorrect color scheme. B&O towers were tan with dark brown trim, not beige and red.)

While these watchmen worked hard, they could not prevent all of the accidents. Some people ignored the crossing gates and were struck by trains. (One of the best-remembered photos in The Daily News from the 1950s shows the pastor of St. Peter's Church trying to give last rites to the victim of just such a crash.) Others crawled under or between stopped trains, and were crushed when the trains unexpectedly began moving. McKeesport averaged 27 train accidents per year between 1927 and 1936, including numerous fatalities.

Not surprisingly, there were several plans proposed, as early as World War I, for getting the B&O out of McKeesport's collective hair.

|

|

|

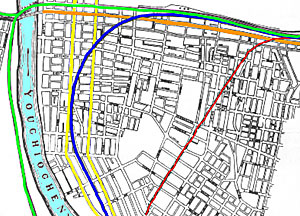

The proposed railroad tunnel under McKeesport is shown in red, the B&O tracks in blue, and the P&LE in green. Market and Walnut streets are highlighted in yellow, while Lysle Boulevard is highlighted in orange. (From collections of Hillman Library, University of Pittsburgh.) |

|

The Tunnel: The B&O proposed building a tunnel under McKeesport for its railroad tracks. The south entrance would have been in Christy Park near the 15th Avenue Bridge. Trains would have exited near McKeesport Hospital, and a new passenger station would have been erected along Fifth Avenue near the foot of Evans Street. The railroad liked the tunnel because it would have avoided grade crossings and would have kept the railroad's trip through McKeesport short, but the cost proved prohibitive. An estimate in the late 1930s put the cost at $7 million, or about $70 million in 2001 dollars.

The Viaduct: Several railroads in the Northeast, confronted with similar problems as the B&O in McKeesport, had erected viaducts through cities, notably in Cleveland and New York. One seriously discussed proposal would have elevated the railroad tracks through Downtown along the existing B&O right-of-way. This would have required tunnels and passageways to be opened at each of the street and pedestrian crossings. The concrete walls necessary to support the viaduct would have been as high as a two-story building in some places. The cost was estimated at $5.5 million, or more than $52 million today.

The Move: A retired railroader living in McKeesport, James A. Fulton, proposed relocating the tracks to Water Street along the Youghiogheny River to avoid the Downtown area altogether. Most of the buildings along the waterfront would have been demolished. The Lysle Boulevard approach to the Jerome Avenue Bridge would have been realigned slightly. The P&LE and B&O would have then shared a steel railroad viaduct along Fourth Avenue, much like the elevated commuter trains in Chicago and New York. The cost of that plan was estimated at $6 million, or more than $57 million by today's standards.

The Cut: There was a proposal at one point to dig a "trench" or "cut" all the way from Guffey Hollow in North Huntingdon Township, through Versailles Township (White Oak) and connect the tracks with the B&O near the current McKeesport-Duquesne Bridge. When someone pointed out that the excavation at some point would have required cuts deeper than those made for the Panama Canal, the plan was shelved.

Obviously, none of the plans were completed, for a variety of reasons, most notably the cost. Then, too, the Baltimore & Ohio was reluctant to agree with any plan that required it to move its tracks to a longer route, even by a few miles.

Perhaps the simplest plan was the one that was finally adopted: Relocating B&O trains to the P&LE in Versailles, rather than in McKeesport. In retrospect, it's hard to understand why that compromise was so difficult to achieve. Maybe it's because the P&LE's tracks through Port Vue were still pretty congested in the 1950s, or maybe it was simply a matter of pride among B&O officials that they didn't want to be a tenant on someone else's tracks. Or, maybe the B&O just didn't want to foot the bill for the new bridge that was eventually built across the Youghiogheny River in Versailles.

In any event, when Allegheny County agreed to contribute part of the construction cost toward the bridge, that was the plan that was finally agreed upon. A new train station --- really a metal pre-fab building --- was erected on Fourth Avenue behind the Eat'n Park, and served until Port Authority opened its new transit center in 1981. The old B&O station was demolished, and the tracks through Downtown were torn up.

It's probably a good thing that none of the viaduct plans were implemented. A viaduct through Downtown would have created a sort of "Great Wall of China" that no doubt would have attracted graffiti artists and squatters, as such railroad viaducts have done in other cities.

|

| Architect’s rendering and Lysle Boulevard elevation of the proposed “McKeesport Union Station” that would have been built if the B&O and P&LE had been placed on a viaduct. (From collections of Hillman Library, University of Pittsburgh.) |

The only downside, perhaps, was that McKeesport lost out on the chance for a spiffy Art Deco "Union Station" that, at one point, was proposed for Lysle Boulevard. It would have served both P&LE and B&O. The rear of the station would have been against the railroad viaduct, and passengers would have reached the trains via stairways or elevators. The two-story brick and concrete structure would have included a reflecting pool in front, a big glass-walled passenger waiting room, and space for post office and Railway Express facilities. That may be for the best; such a station would have become a liability after the B&O stopped providing passenger service in 1971.

The remaining B&O tracks, which dead-ended near the 15th Avenue Bridge, became a siding that served Potter-McCune Co's grocery warehouse, the G.C. Murphy Co. warehouse, Fort Pitt Steel Casting Co., U.S. Steel's Christy Park Plant, and a few other customers. Eventually, even the siding was abandoned, and the tracks became part of the Youghiogheny River hiking and biking trail.

The only remaining evidence of the B&O through Downtown are a number of buildings --- like the old Immel's store on Fifth Avenue, the Sunray Electric warehouse on Walnut --- with walls that form odd-shaped angles. They once butted up against the railroad tracks that no longer exist.

Cross country trains still travel through McKeesport dozens of times per day, of course. In 1987, CSX Transportation absorbed the B&O, and a few years later, purchased the P&LE's tracks through McKeesport and elsewhere. CSX completed a multi-million dollar rehabilitation of the P&LE that left it in better shape than it had been in years. The last daily commuter trains to McKeesport ended on April 28, 1987, when Port Authority discontinued its daily PATrain, and though Amtrak still passes through the city every day, it no longer stops.