It was a rare quiet moment during three days of celebrations for Paige, whose heroism during the Battle for Henderson Field on the Solomon Islands won him the United States' highest military honor in 1943. He was the 10th Marine in the corps' history to be recognized with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Paige, who died just after Veteran's Day, 2003, was a son of Serbian immigrants and a graduate of McKeesport High School.

Unable to find a job during the Great Depression, Paige joined the Marines in 1936. He had to hitchhike 200 miles to the nearest Marine Corps recruiting station in Baltimore.

Posted to the battleship USS Wyoming, Paige would serve the peacetime Marine Corps in China and the Philippines.

But his finest hour came on Oct. 26, 1942, as a platoon sergeant during the third and final land battle of the Solomon Islands, east of New Guinea.

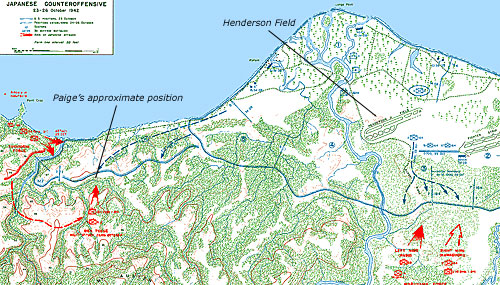

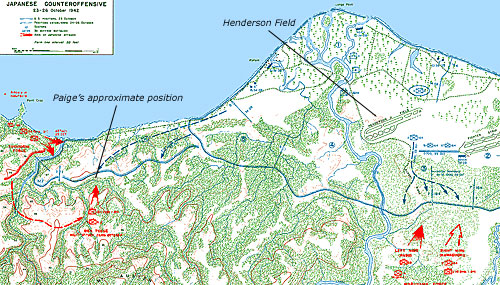

In August, U.S. and allied forces had captured several important Japanese bases, including an airstrip on the island of Tulagi that they renamed Henderson Field. Now, the Japanese wanted that territory back.

|

|

|

The battleship USS Wyoming, as it appeared when Paige was onboard. (U.S. Navy photo) |

|

|

Holding the Solomons

After the Marines repulsed several smaller invasion forces, some 15,000 Japanese soldiers landed in the Solomons, including 7,000 whose mission was to retake Henderson Field.

The fight for the airstrip began Oct. 24 and continued for three days. Japanese troops on the ground were supported by carrier-based bombers and fighters. Though they inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans, they also suffered heavy losses and failed to dislodge the Marines from their defensive positions.

Early on the morning of Oct. 26, troops led by Japanese Army Col. Akinosuka Oka began one last, bloody assault on the U.S. Marines defending the jungle to the extreme west of Henderson Field.

Under the command of then-Platoon Sgt. Mitch Paige, a machine gun section of 32 Marines from F Company, 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, were holding a tiny sliver of ridge above the Matanikau River. As Oka's troops came up the hill, the Marines opened fire with their .30-caliber Browning M1919s.

But the Japanese kept coming, opening up on the Marines with mortars and machine guns. Naval historians later concluded the Marines of Paige's section had been outnumbered 30-to-one.

All around him, Paige's men were being cut down; as Marines fell, one by one, Paige would move to each man's position, take up his machine gun, and keep firing.

At one point, several Japanese soldiers charged at him with bayonets. Paige, sustaining a deep wound on his left hand, fought back with his combat knife.

Pacific Theater's 'Turning Point'

Bleeding, bruised, waiting for reinforcements and virtually alone, Paige spotted a Japanese soldier taking aim at him with a machine gun from less than 20 yards away. Paige tried to fire, but his weapon jammed. Thirty rounds streaked past his head before Paige could return fire, killing the Japanese soldier.

Paige then spotted a Japanese command post and attacked; three rounds fired by the Japanese commander glanced off of Paige's helmet before Paige finally slew the man.

At dawn, the 2nd Battalion's executive officer, Maj. Odell Conoley, came to Paige's position to see how many Marines were holding the hill. He found only Paige. Quickly gathering reinforcements — including a cook and a bandsman — Conoley sent them to Paige's aid.

When they arrived, Paige ordered them to fix bayonets and led a final attack that forced the Japanese into retreat. Japanese Lt. Gen. Harukichi Hyakutake ordered his troops to withdraw from the hill at 8 a.m. local time.

The Marines later counted 300 dead Japanese soldiers around Paige's position. Total American casualties, including the original F Company troops and the reinforcements, were 14 dead and 32 wounded.

Two weeks later, his wounds healing, Paige met with Maj. Gen. A.A. Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division.

"Son, that was an important hill that you and your men held," he said, shaking Paige's hand. "It was the last major Japanese effort to dislodge us and capture the airstrip."

U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur later called it "the turning point" of the war in the Pacific. In December, Paige was promoted to second lieutenant.

(Official U.S. Navy map)

Sent Medal Home in Cigar Box

News that Paige had been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor reached McKeesport in June of 1943. Paige had wrapped it up in a cigar box and mailed it home to his folks.

The citation read:

- Alone, against the deadly hail of Japanese shells, he fought with his gun and when it was destroyed, took over another, moving from gun to gun, never ceasing his withering fire against the advancing hordes until reinforcements finally arrived. Then, forming a new line, he dauntlessly and aggressively led a bayonet charge, driving the enemy back and preventing a breakthrough in our lines. His great personal valor and unyielding devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.

In Washington, U.S. Rep. Samuel Weiss, Democrat from Glassport, wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, asking that Paige receive several days' leave to come home for a celebration.

It was nearly a year before Paige could make it home; a planned celebration in May 1944 was cancelled because Paige couldn't get a flight from the Pacific Ocean to the West Coast.

When Paige finally arrived, he came one day before a series of tornadoes ripped through Western Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia. The twister or twisters that struck the Mon-Yough area caused millions of dollars in damage in the city, Port Vue, Dravosburg, West Mifflin, Liberty Borough, and Elizabeth Township. More than 150 people were hurt and 18 were killed.

Fully aware that Paige could only be spared from the Marines for brief period of time, organizers decreed that the ceremonies would continue despite the storm damage.

The celebrations turned out to be almost as exciting as the tornadoes.

Motorcade Took All Day

A June 27 ticker-tape parade down Fifth Avenue, Downtown, was just the beginning. At 9:45 a.m. the following morning, a motorcade carrying Paige, his family, and selected military dignitaries departed the Morton Plan section of West Mifflin and headed through Homeville, Duquesne, Munhall, the Turtle Creek valley, Versailles Township (present-day White Oak), Liberty, Elizabeth, Clairton, and back to Paige's childhood home on Camden Hill, near U.S. Steel's Irvin Works.

"I'll never be able to go back to camp after this," Paige teased his parents’ neighbors when they asked for autographs.

The trip took all day, and no wonder: in every town, the motorcade stopped at honor rolls so that a weary Paige — his skin yellowed by atabrine, an anti-malaria medication — could greet well-wishers and accept tributes.

In Homestead, the parade stopped for a rally where residents purchased $230,000 in war bonds. Paige was greeted by West Mifflin School Superintendent Harry Bruce and George Lloyd, president of the Monongahela Trust Co., who presented him with war bonds totaling $1,200.

In Versailles, the motorcade made an unexpected stop so that Paige could run into the A&P. "I just want to smell a grocery store again," he said.

The following night, 750 people packed the ballroom of the Alpine Hotel on Crooked Run Road in North Versailles Township for a banquet in Paige's honor, where attendees purchased another $200,000 in war bonds.

A week later, Paige was in Chicago for a nationwide radio broadcast over the Mutual network, before he returned to the Pacific front, where he fought in the battle of New Britain.

Medal 'Belongs to 33 People'

After the war, Paige served tours in Cuba and China before eventually becoming an instructor and recruiting officer in North Carolina and California.

It was 15 years before he could discuss the events on Guadalcanal. Paige told one interviewer that his Medal of Honor belonged "to 33 people" from F Company who were killed in the Battle of Henderson Field: "The greatest heroes were those guys who didn't survive."

After being placed on the disability list in November 1959, Paige settled in California. There, his reputation was briefly tarnished when he hooked up with a group of rabid anti-Communists aligned with the John Birch Society. News cameras were rolling in 1961 when Paige gave a fiery speech condemning Chief Justice Earl Warren as "a Commie" who "should be taken out and hanged." (He later apologized and retracted the statement.)

Upon his official retirement from active duty in 1964, Paige worked in research and development for defense contractors, helping to create miniaturized rockets, rescue devices, and the Universal Paige Inflatable Tent, which was deployed with troops in Vietnam.

Hunting Down Frauds

Then, in the early 1990s, Paige became famous again. This time, he was waging a different kind of battle — he was working with the FBI to hunt down people who were selling fake Congressional Medals of Honor or falsely claiming to be Medal recipients.

Then, in the early 1990s, Paige became famous again. This time, he was waging a different kind of battle — he was working with the FBI to hunt down people who were selling fake Congressional Medals of Honor or falsely claiming to be Medal recipients.

Instead of charging into celebrations or parades where the scam artists were present, Paige would quietly pull the imposters aside and confront them before they attempted to trade on the medal's prestige to cadge free meals and other privileges.

"There are only 207 of us living," he told a reporter in Riverside, Calif., in 1992. "We all know each other personally. We get together, and we talk frequently. When one of these phonies shows up and wants to join us at a public gathering, we all know he's an impostor."

Paige's efforts eventually led the federal government to increase the penalties for selling fake military honors from $250 to $100,000 and one year in prison.

Honored Late in Life

His quiet, persistent crusade led to news stories, and a new generation heard about Mitch Paige's bravery. West Mifflin council named a community park in his honor in 1996.

But perhaps his most unique recognition came in 1998, when Hasbro commissioned a special "G.I. Joe" figure whose face was modeled after his own.

In March 24, 2003, at age 84, Paige attended a ceremony in Jacksonville, Fla., where the Boy Scouts of America presented him with an Eagle Scout medal.

Paige would have received the leadership and service award back in McKeesport in 1936, but he'd left town to join the Marines, and the honor was forgotten after his paperwork was misplaced by the Scouts. An FBI agent volunteered to confirm that Paige was eligible for Scouting's highest achievement.

Weakened by heart disease, Paige died eight months later, age 85, and was buried in Riverside National Cemetery, 70 miles east of Los Angeles.

Not long after his death, Paige's adopted hometown of La Quinta, Calif., named a middle school for him.

An exhibit at the Marines Corps air base in Twentynine Palms, Calif., also honors the legacy of one of the Mon Valley's greatest military heroes ... the Marine who single-handedly repelled an enemy attack, and then came home to do his own laundry.

: : :

© 2008 Jason Togyer, all rights reserved. No portion of this story may be republished without express permission, with the exception that short excerpts may be reproduced for review or commentary purposes. Published at www.tubecityonline.com by Tube City Community Media Inc., P.O. Box 94, McKeesport, PA 15134.

Then, in the early 1990s, Paige became famous again. This time, he was waging a different kind of battle — he was working with the FBI to hunt down people who were selling fake Congressional Medals of Honor or falsely claiming to be Medal recipients.

Then, in the early 1990s, Paige became famous again. This time, he was waging a different kind of battle — he was working with the FBI to hunt down people who were selling fake Congressional Medals of Honor or falsely claiming to be Medal recipients.