The ‘Tinplate Liar’ of McKeesport

A McKeesport businessman helped build the U.S. steel industry ... and send William McKinley to the White House

© 2007 Jason Togyer, all rights reserved.

Background | Preserver of Industry | A Welshman Arrives |

Salvation, Then Struggle | The ‘Illogical’ Tariff | ‘Tinpot Lobbyist’

McKeesport Fights Back | Merger and Aftermath

It's a familiar story to anyone from Western Pennsylvania. Cheap foreign imports are destroying an American industry, leading to plant closures and shut downs. Steel companies and Mon Valley community leaders unite to lobby federal officials for stronger tariff regulations, but manufacturers --- who like the artificially low prices the imports provide --- oppose any changes. Mergers and layoffs sweep the industry before reform legislation finally levels the playing field.

But this isn't the present day, or even the 1970s. It happened more than 100 years ago. And if it hadn't been for a McKeesport councilman who was denounced in national media and on the floor of the United States Congress as a "tinplated liar," America's infant iron and steel industries might have had very sickly childhoods.

Though he lacked the technical inventiveness of Captain William Jones or the ruthlessness of Andrew Carnegie, German immigrant William C. Cronemeyer had political and business skills that were every bit as important in the Mon-Yough area's development as "the steel capital of the world."

Background

Molten iron can be wrought or cast into shapes and structures, but its uses are otherwise fairly limited. Since raw iron can't be soldered, it's not easy to connect two pieces together except by mechanical means such as screws and rivets. And without some protective coating on the surface, bare iron surfaces will quickly corrode, or rust.

One way to protect the surface of iron is to coat it with a cheaper, base metal like tin, and blacksmiths were "tinning" iron in ancient times. But the tinning was done after the iron was hammered or cast into a useful shape.

It wasn't until the 17th century that blacksmiths began tinning the iron before they fabricated it into a shape. They would beat iron into flat sheets, coat it with tin, and then bend the tin-plated iron into tools, pots and pans, or boxes.

The first sustained continuous production of "tinplate" came in Germany's Ruhr valley, and the practice spread to England and Wales, where tin was plentiful.

|

|

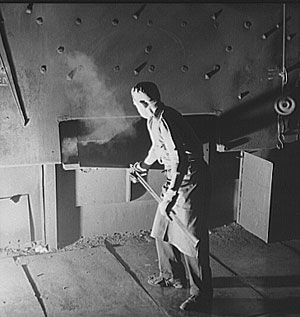

A worker at a tinplate mill in Washington, Pa., pulls a sheet of iron from a furnace. (Office of War Information photo by Jack Delano, circa 1940. Library of Congress collection.) |

|

At first, the iron plates were forged by hand, but inventors soon developed steam and water-powered mills that could squeeze hot iron bars between hard rollers to flatten them into sheets. Each hot iron sheet passed through smaller and smaller rollers until reaching the desired thickness.

Raw iron plates were allowed to cool, bathed in acid to remove surface rust, then washed in water. Workers then baked them in a furnace again (a process called "annealing"), allowed them to cool, and rolled them again to polish the surface. Then they were heated and bathed in acid again before being soaked in pots of molten tin.

By convention, tinsmiths rolled each sheet to a size of 14-by-20 inches. Each weighed just a bit less than one pound; 112 sheets could be packed into a standard wooden crate and comprised a 100-pound box of tinplate, or a "hundredweight." The mills of England and Wales were soon exporting 5 million pounds of tinplate per year; in addition to kitchenware, the newly-developed "tin cans" of fruit and meat were becoming popular items for travelers (once canners figured out how to sterilize the contents and prevent bacteria from spoiling them).

Preserver of U.S. Tinplate

The man who Cronemeyer later called the "preserver of the U.S. tinplate industry" was born in Lauffen, Germany, on Feb. 12, 1810. John Henry Demmler became an apprentice tinsmith at age 18, working in Stuttgart, Geneva, and Berne before sailing to the United States in May 1834.

According to an early biography, he plied his trade in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington and Alexandria, Va., where he became an ardent abolitionist after seeing a group of African-American slaves being led away in shackles.

Having saved a sizable sum of money, Demmler was apparently planning to return to Germany when he decided to take a vacation and see the "western frontier," traveling by stagecoach to Cumberland, Md., and Pittsburgh, called the "gateway to the West" because of its position at the headwaters of the Ohio River.

Demmler was smitten by the rapidly growing city. Besides offering excellent river transportation, it was close to coal mines and iron ore deposits, all of which helped fuel small iron works and foundries around Pittsburgh. Demmler took a job at the W.B. Scaife Iron Works on Wood Street, which made lanterns and other products.

In 1836 he married Christina Breitenstein, a Bavarian immigrant; they eventually had 11 children. Soon Demmler had opened his own tinsmith's shop at the corner of Sixth and Smithfield streets and was shipping products around the country, first by stagecoach and riverboat, later by railroad.

His oldest sons, Henry and Louis, joined him at the shop before opening their own tin works, Demmler Brothers, a few blocks away, where they manufactured pots, pans and other housewares.

A Welshman Arrives

But most tinplate was still being imported from England, where long-established mills could turn out a cheaper, more reliable product than any American factory.

Then in 1873, a tinsmith from South Wales, William Oak Davies, arrived in the United States with what he claimed was a new, simplified process for making tinplate. He obtained a U.S. patent and newspapers were filled with stories about Davies' revolutionary methods. J.D. Strouse, a former Pittsburgh grocer who had become a real-estate developer and banker, bought the patent and chartered a new corporation, the United States Iron & Tin Plate Co., with Davies as superintendent.

The Demmler family bought stock in hopes of securing a cheap, local supply of tinplate. A 10-acre farm was purchased near McKeesport, and that summer construction began on a mill that would use the amazing new Davies process. The Wall Street panic of 1873 temporarily dried up credit and investment, forcing construction to be suspended. Work resumed until the contractors absconded with the money, shutting construction down again.

Both times, John Demmler pledged his own business and property as collateral so that work could continue, and the McKeesport plant began operations in August 1874. That's when Strouse and Demmler learned that Davies was a fraud. His machinery didn't work as advertised and his methods produced poor quality tinplate. Worse yet, Davies' abusive personality alienated the workers, who went out on strike. When the mill began losing money, Davies was forced to resign and operations halted in November.

Demmler Brothers still needed a supply of tinplate, so John Demmler sold some property and his own company, using the proceeds to pay off $50,000 of the tinplate company's debt and to guarantee another $50,000 in credit. The assistant superintendent of an iron works in Leechburg, Armstrong County, was hired to run the McKeesport mill, and Demmler was named president of U.S. Iron & Tin Plate.

A new railroad station on the Baltimore & Ohio's line between Pittsburgh and Connellsville was named in the family's honor, and the surrounding area became known as "Demmler." A growing residential area above the factory was formally known as "Highland Grove," but unofficially, McKeesporters were calling it "Tin Plate Hill."

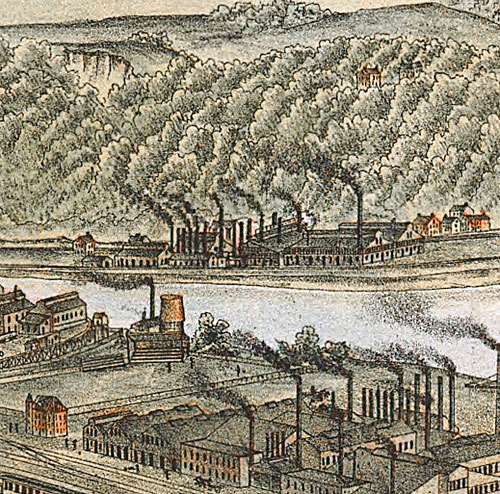

An 1893 view of the United States Iron & Tin Plate Co., located on the south side of the Monongahela River at the McKeesport city limits. Carnegie Steel Co.’s Duquesne Works is in the foreground. From a map entitled “City of McKeesport & vicinity” by H. Morgenroth. (Library of Congress collection)

Salvation, Then Struggle

In 1875, the combined efforts of the new management enabled the mill to finally start turning out good tinplate for roofing and other products, which they sold for about $10 a box, and the plant began returning steady profits.

That caught the attention of the companies that imported English and Welsh tinplate, and not surprisingly they fought back. They offered to undersell any American tinplate by at least 25 cents per box and eventually flooded American shores with tinplate as cheap as $4 per box. The McKeesport mill and two other new American tinplate factories soon found their customers drifting away again.

But Demmler and the U.S. tinplate industry had an unlikely secret weapon in the form of a former dry-goods clerk in his late 20s named William C. Cronemeyer.

Born in 1847 in Hovedissen, Germany, Cronemeyer emigrated to the United States at age 22 and settled in western Pennsylvania, where he had relatives.

In 1873 he went to work for U.S. Iron & Tin Plate and during the reorganization effort the following year was named secretary of the corporation by Demmler, a fellow German immigrant. As cheap Welsh and English tinplate flooded the U.S. market, Cronemeyer began hounding congressmen from Pennsylvania to help correct a ridiculous interpretation of American import law.

Theoretically, tariffs enacted during the Civil War should have made imported tinplate more expensive than domestic. But the wording of the tariffs was ambiguous, and Abraham Lincoln's secretary of the treasury, William Pitt Fessenden, ruled that according to the language used, tin-plated iron sheets were only subject to import tax if they were coated with some other metal on top of the tin --- a process that would be redundant and wasteful.

The 'Illogical' Tariff

|

|

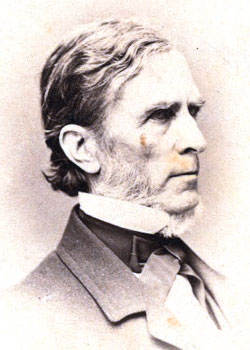

Secretary of the Treasury William Pitt Fessenden. Despite his middle name, Fessenden was no friend to Pittsburgh’s iron and steelworkers; his “ignorant” decision on the tinplate tariff stymied the industry for more than 20 years. (Mathew B. Brady photograph from Library of Congress collection.) |

|

"Evidently, Mr. Fessenden ... was ignorant of the consistency of tinplate," Cronemeyer said later. Subsequent secretaries of the treasury admitted Fessenden's ruling was "illogical" but refused to overturn it, saying that Congress would have to clarify the law.

By 1877, only a few American tinplate mills remained in operation, and a recession that year drove them into bankruptcy. John Demmler was urged to foreclose on the mill in McKeesport and sell the assets, Cronemeyer said, but "was determined not to let it go under." Though the existing stock in U.S. Iron & Tin Plate Co. was virtually worthless on the open market, Demmler began buying options on the outstanding shares. He soon held options to buy about 90 percent of the company.

To keep the mill afloat, Cronemeyer and Demmler stopped making tinplate and instead turned out small sheets of "black iron" that were sold to enamel-plating companies; these companies made bowls, pots and other products and coated them with molten glass to form a hard, protective surface. "Thus we managed to keep our company above water," Cronemeyer said. The Demmler mill soon employed 300 men.

Then, two tragedies struck. In 1882, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, which represented skilled trades in the mills around Pittsburgh, went out on a general strike, closing the McKeesport plant.

The resulting shutdown drove U.S. Iron & Tin Plate Co. into insolvency; Demmler foreclosed on the mill, then bought the company's assets out of sheriff's sale, reorganizing U.S. Iron & Tin Plate Co. as a limited partnership controlled by his sons and several other investors.

No sooner had the mill gone back into operation than a $100,000 fire gutted the entire plant; on the morning of Feb. 18, 1883, sparks generated by the plant's boiler house set the roof ablaze. The flames also destroyed a nearby railroad trestle. Insurance covered about half of the damage; the Demmlers paid to put the plant back into operation.

The 'Tinpot Lobbyist'

Elected secretary of an industry trade group, Cronemeyer relentlessly badgered Congress to enact a new tariff. Year after year, he and other iron and steel manufacturers traveled to Washington to testify before the House Ways and Means Committee; year after year, the committee nodded sympathetically, but failed to give the tinplate companies any relief. In the meantime, the Demmler mills survived on sales of sheet iron and a small trade in some tinplate.

Cronemeyer was becoming a pillar of the community as well, elected to McKeesport Borough Council (the municipality had not yet received a city charter) and serving on the committee that created McKeesport Hospital. He also helped found the chamber of commerce.

|

|

U.S. Rep. William McKinley, a Republican from Canton, Ohio, supported higher tariffs to protect domestic industry and generate more revenue for the federal government. McKeesport industrialist William Cronemeyer was a strong booster. (Library of Congress collection.) |

|

Finally, after more than a decade of lobbying, Cronemeyer found a congressman willing to act. In 1888, Republicans won control of the presidency and both houses of Congress, and U.S. Rep. William McKinley of Ohio became chairman of the Ways and Means Committee.

A native of Canton, where many new iron and steel mills were being erected, McKinley took a particular interest in the tinplate industry's problems. He vowed a comprehensive overhaul of American tariffs and import duties. Because there was no personal income tax, tariff revenue funded virtually all of the federal government’s revenues. And McKinley believed it was vital to America’s national interest to develop its own domestic industries.

Under the so-called McKinley Tariff, not only would imported tinplate finally be subject to tariffs, the rate would more than double. American manufacturers reacted with outrage. After all, they were consuming roughly 80 percent of the entire output of the tinplate mills of Wales and England --- roughly 300,000 tons.

McKeesport Fights Back

Opponents of the McKinley Tariff claimed that tinplate couldn't be successfully manufactured in the United States because America's immigrant workers didn't have the right skills. Balderdash, Cronemeyer said; a "person of ordinary intelligence could be trained in that business in six months."

Then they argued --- with some justification --- that higher tariffs would be passed along to American consumers in the form of higher prices. Cronemeyer replied that allowing tinplate to be imported without any taxes at all was keeping the price of the foreign product artificially low.

Tinplate importers also claimed that the American-made product was "inferior." The Demmler mill made "very poor tin," alleged an executive at Phelps, Dodge & Co., which imported English tin. "As a matter of fact, there hasn't been a box of merchantable tin made in this country for years," he said.

That was clearly false, and Cronemeyer could prove it. He ordered the Demmler plant to stamp out samples of tinplate and mail them to prominent Americans, including President Benjamin Harrison, a Republican sympathetic to McKinley and his tariff fight.

"I have no skill in determining the character of this work, but it seems to be eminently satisfactory," the President wrote back to Cronemeyer. "I thank you for this evidence that a new industry has been established in the United States."

To the Washington Post and other newspapers, Cronemeyer sent a New Year's card engraved into a sheet of tinplate:

Don't be afraid --- it is tin-plate,

Americans reduced it;

We wish to tell, that we as well

As foreigners produced it.Don't be afraid of evil fate

To poor man's dinner bucket;

He always will have stuff to fill ---

So long's free trade don't chuck it.Don't be afraid, we'll relegate

The foreigners to back seats, sir;

American girl, she is a pearl ---

American tin will suit her.

The 'Tinplate Liar'

It made for good newspaper copy, but Democrats and other McKinley opponents weren't convinced. Ohio Governor James F. Campbell was a Democrat and a critic of McKinley, and Cronemeyer sent him a sample of McKeesport-made tinplate. Campbell took it with him on a speaking trip, waving it at crowds and calling it "alleged tinplate." He sneered that he would have "some tin horns made out of it."

Editorials in the New York Times attacked McKinley as a "fanatic" and a "lunatic" and branded the Mon Valley as "the tin-plate lie center" of the United States. Cronemeyer's assertions were branded as "far from the truth." Propaganda from manufacturers and tinplate importers called Cronemeyer "a tinpot lobbyist," while Puck Magazine derided Cronemeyer as "the tinplate liar" and portrayed Harrison as "Little Tin Ben."

Despite the smear campaign, Cronemeyer's persistence carried the day, and in 1890 Congress voted along party lines to approve the "McKinley tariff." That helped the American iron and steel industry, but all of the anti-tariff speeches and reports turned the public solidly against the Republican Party, which lost 93 seats in the House of Representatives in the November mid-term elections.

Among those defeated was McKinley.

Nevertheless, the tariff went into effect on June 30, 1891, and the impact was immediate. Within two years, 41 American companies were in business and had manufactured 43 million pounds of tinplate. Contrary to arguments made against the tariff, a competitive domestic market actually forced the price of tinplate down.

(The effect on Wales, sadly, was almost as predictable; with American manufacturers entering the field on a daily basis, the tinplate industry in the U.K. was devastated. More than 20,000 Welsh tin workers were out of work; some emigrated to the United States to practice their trade.)

And in Ohio, McKinley got the last laugh; he ran against Campbell for governor of Ohio and was elected by a margin of 19,000 votes. The election was widely seen as a public vote of confidence in the tinplate tariff, and the governor's office served as the platform for McKinley's eventual campaign for the presidency in 1896.

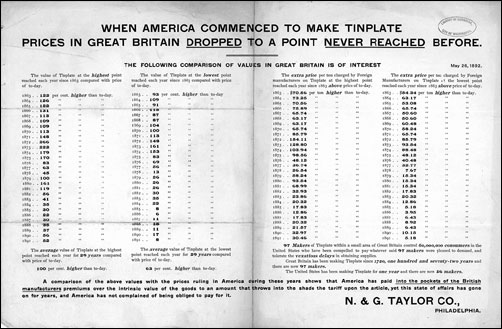

A pamphlet published in 1892 argues that the McKinley tariff had actually forced British tinplate manufacturers to lower their prices. (Click to enlarge. Library of Congress collection.)

Merger and Aftermath

John Henry Demmler didn't live to see the rapid growth of the American tinplate industry; he died in the summer of 1893. But the industry was booming so much that companies began duplicating each other's efforts, and consolidation followed. In 1897, Cronemeyer and other industry leaders formed the American Tin Plate Co. to merge 39 different companies, including U.S. Iron & Tin Plate Co. in McKeesport, which then employed about 1,000 men.

In 1900, American Tin Plate was acquired by the new United States Steel Corporation, and four years later it was absorbed into a new U.S. Steel division, the American Sheet & Tin Plate Co.

Now 30 years old, the Demmler plant was also among the smallest in the new corporation. U.S. Steel owned 50 newer tinplate lines in New Castle, Pa.; 20 at a plant in Elwood, Ind.; and 14 each in Pittsburgh and Martin's Ferry, Ohio.

The Demmler plant was closed and the machinery dismantled; in 1916 the property was acquired by the neighboring Firth-Sterling Steel Co. Like U.S. Iron & Tin Plate Co. in the 1870s, Firth-Sterling was experimenting with a new technology that had been developed in England. It was called stainless steel.

|

|

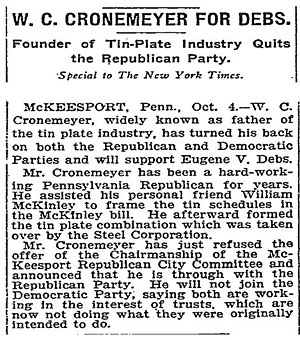

From the New York Times, Oct. 5, 1908. |

|

Cronemeyer retired from the steel industry, investing his savings in real estate and coal mines. In 1908, he made national headlines when he announced he was dropping out of the Republican Party to support Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs for president. Both the Republicans and the Democrats were "working in the interest of trusts," Cronemeyer said.

He was living on Elm Street in Bridgeville, Pa., when he became ill and was transported to McKeesport Hospital, where he died on the morning of May 22, 1934, age 86.

Honorary pallbearers at his interment in McKeesport-Versailles Cemetery included several of the Demmler children and a Duquesne man, Edwin R. Crawford, who had once worked at the Demmler tinplate factory.

At the time, Crawford's firm, McKeesport Tin Plate Company, was cranking out enough tinplate to furnish one out of every 10 cans sold in the United States.

The "tinplate liar from McKeesport" was truly vindicated.

: : :

Sources

"Another View of Tin Plate," The Washington Post, June 18, 1891, p. 4.

Cronemeyer, William C. John Henry Demmler, The Preserver of the Infant American Tin Plate Industry (Unpublished manuscript in files of McKeesport Heritage Center, McKeesport, Pa.)

—, The Development of the Tin Plate Industry. (Unpublished manuscript in files of McKeesport Heritage Center, McKeesport, Pa. Undated, but circa 1905.)

"Cronemeyer on Tin Plate," The New York Times, March 17, 1892, p. 4.

"Curious Paralysis of Memory," The New York Times, July 22, 1893, p. 4.

"Drift of Congressional Work," The New York Times, Jan. 19, 1882, p. 1.

"Great Tin Plate Trust," The New York Times, Dec. 16, 1898, p. 14.

"In The Hotel Lobbies," The Washington Post, Aug. 21, 1888, p. 4.

"Losses By Fire," The New York Times, Feb. 19, 1883, p. 5.

"The McKinley Tariff," Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007.

Moody, John, The Truth About The Trusts (New York: Moody Publishing Co., 1904), pp. 133-162.

"Mr. Harrison is Grieved," The New York Times, Oct. 22, 1891, p. 3.

"Mr. Plumb on Tin-Plate," The New York Times, Aug. 16, 1890, p. 4.

Nimmo, Joseph Jr., "The Tin-Plate Industry," The Washington Post, May 18, 1891, p. 2.

Old Home Week Book of McKeesport (McKeesport: Old Home Week Committee, 1910)

Pursell, Carroll W. Jr., "Tariff and Technology: The Foundation and Development of the American Tin-Plate Industry, 1872-1900," Technology and Culture, Summer 1962, pp. 267-284.

The Story of Pittsburgh and Vicinity (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, 1908), pp. 188-192.

"Tin Plate Imported," The Washington Post, Oct. 24, 1893, p. 5.

"Tin-Plate Poetry," The Washington Post, Jan. 10, 1891, p. 4.

"The Tin-Plate Romance," The New York Times, Oct. 17, 1890, p. 9.

"The Tin-Plate Situation," Manufacturer and Builder, November 1892.

"The Tin-Plate Swindle," The New York Times, Jan. 3, 1890, p. 4.

---

© 2007 Jason Togyer, all rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without express permission is prohibited. To get permission to republish this article, please send email first initial and last name at gmail dot com, or write to Tube City Online, P.O. Box 94, McKeesport, PA 15134.

Comments, corrections and additions are welcome! Write to first initial and last name at gmail dot com. This article is from tubecityonline.com/steel, the Steel Heritage section of Tube City Online, P.O. Box 94, McKeesport, PA 15134.